The Almas in Mongolian (Altaic) means “wild man,” though possibly derived from ala (“to kill”) + mal (“animals”). The word is found in many southern Mongolian place-names. Unlike the Sasquatch or the Yeti from the descriptions available which seems large and very apelike, the Almas seems smaller and more human. The creature is not currently recognized or cataloged by science. Reports of the Almas are concentrated in the Caucasus and Pamir Mountains of central Asia, and the Altai Mountains of southern Mongolia. Similar reports come from Siberia and the far northeast parts of the Russian republic. Early in the fifteenth century, Bavarian soldier Johannes Schiltenberger was captured by Turks at the Battle of Nikopol, Bulgaria, who placed him in the retinue of a Mongol prince named Egidi.

After returning to Europe in 1427, Schiltenberger wrote about his experiences, which included wildmen. While in the Tian Shan Mountains, he became the first Westerner to see an Almas:

"In the mountains themselves live wild people, who have nothing in common with other human beings. A pelt covers the entire body of these creatures. Only the hands and face are free of hair. They run around in the hills like animals and eat foliage and grass and whatever else they can find."

Sometime in the late nineteenth century, a caravan was resting in the southern part of the Mongolian province of Övörhangay on the way to Hohhot, Nei Mongol Autonomous Region, China, one of the men in the party went to collect the camels that had been set loose to graze. When he did not return, the others went off into the saxaul thickets to look for him. At the entrance to a cave, they found evidence of a struggle and figured an Almas had abducted him. One of the elders suggested they pick him up on the way back from Hohhot, which they did, waiting until the creature emerged from the cave at sundown and shooting it. The rescued man seemed to be insane and died two months afterward.

Sometime in the late nineteenth century, a caravan was resting in the southern part of the Mongolian province of Övörhangay on the way to Hohhot, Nei Mongol Autonomous Region, China, one of the men in the party went to collect the camels that had been set loose to graze. When he did not return, the others went off into the saxaul thickets to look for him. At the entrance to a cave, they found evidence of a struggle and figured an Almas had abducted him. One of the elders suggested they pick him up on the way back from Hohhot, which they did, waiting until the creature emerged from the cave at sundown and shooting it. The rescued man seemed to be insane and died two months afterward.

In April 1906, Soviet scholar Badzar Baradiin reportedly had a brief encounter with an Almas while he was traveling in the Gobi Desert near Badain Jaran, Nei Mongol Autonomous Region, China. However, Michael Heaney considers this story a fiction, based on the fact that there is no mention of the incident in Baradiin’s meticulous diary of the trip; moreover, the actual route was 150 miles east of where the event supposedly took place.

A seven-year-old Almas female was accidentally killed in the Gobi when she set off a crossbow attached to an animal snare. Many people in the sparsely populated area are said to have seen the body, but the locals begged investigators not to talk about it, since crossbow snares were illegal.

The Pamir mountains, lying in a remote region where the borders of Tadzhikistan, China, Kashmir, and Afghanistan meet, have been the scene of many Almas sightings. In 1925, Mikhail Stephanovitch Topilski, a major-general in the Soviet army, led his unit in an assault on an anti-Soviet guerilla force hiding in a cave in the Pamirs. One of the surviving guerillas said that while in the cave he and his comrades were attacked by several apelike creatures. Topilski ordered the rubble of the cave searched, and the body of one such creature was found. Topilski reported:

"At first glance I thought the body was that of an ape. It was covered with hair all over. But I knew there were no apes in the Pamirs. Also, the body itself looked very much like that of a man. We tried pulling the hair, to see if it was just a hide used for disguise, but found that it was the creature's own natural hair. We turned the body over several times on its back and its front, and measured it. Our doctor made a long and thorough inspection of the body, and it was clear that it was not a human being."

In 1927, travelers left a caravan unattended while they went to look for a camel that had dropped back. Upon their return at daybreak, they found several Almas warming themselves by the dying campfire. The creatures had eaten some dried dates and sweets but had left the jars of wine untouched.

A monk named Dambayorin was traveling across the Gobi in 1930 when he saw a naked child in the distance. When he got closer, he saw it was covered with red hair, realized it was an Almas, and fled in terror.

An entire skin of an Almas is said to have hung in the temple of the monastery at Baruun Hural, Mongolia, in 1937. It had humanlike legs and arms and long hair hanging from its head. The Almas had been killed in the Gobi by the hunter Mangal Durekchi and given to the lamas. A Mongolian pharmacist named Nagmit was in the mountains with two Kazakhs when they came upon an Almas. They shouted at it, offering it food and clothing, but it kept its distance. When they shot at it, intentionally missing, the creature merely seemed curious, then departed.

In 1957, Alexander G. Pronin, a hydrologist at the Geographical Research Institute of Leningrad University, participated in an expedition to the Pamirs, for the purpose of mapping glaciers. On August 2, 1957, while his team was investigating the Fedchenko glacier, Pronin hiked into the valley of the Balyandkiik River. Pronin stated:

"At noon I noticed a figure standing on a rocky cliff about 500 yards above me and the same distance away. My first reaction was surprise, since this area was known to be uninhabited, and second was that the creature was not human. It resembled a man but was very stooped. As i watched the stocky figure move across the snow, keeping its feet wide apart, and its forearms were longer than a human's and it was covered with reddish-grey hair."

Pronin saw the creature again three days later, walking upright. Since this incident, there have been numerous wildman sightings in the Pamirs, and members of various expeditions.

In 1963, Ivan Ivlov, a Russian pediatrician, was traveling through the Altai mountains in the southern part of Mongolia. Ivlov saw several humanlike creatures standing on a mountain slope. They appeared to be a family group, composed of a male, female, and child. Ivlov observed the creatures through his binoculars from a distance of half a mile until they moved out of his field of vision. His Mongolian driver also saw them and said they were common in that area. After his encounter with the Almas family, Ivlov interviewed many Mongolian children, believing they would be more candid than adults. The children provided many additional reports about the Almas. For example, one child told Ivlov that while he and some other children were swimming in a stream, he saw a male Almas carry a child Almas across it.

In 1980, a worker at an experimental agricultural station, operated by the Mongolian Academy of Sciences at Bulgan, encountered the dead body of a wildman:

"I approached and saw a hairy corpse of a robust humanlike creature dried and half-buried by sand. . . . The dead thing was not a bear or ape and at the same time it was not a man like Mongol or Kazakh or Chinese and Russian."

Possible explanations suggested by Mark Hall and Loren Coleman, perhaps the Almas is a surviving Homo erectus, The nearest known fossils are the Zhoukoudian Peking man remains found north of Beijing in the 1920s. The browridge, flat nose, absent chin, and robust jaw match Almas descriptions. H. erectus used a primitive (Acheulean) toolkit of hand axes and other bifacial stone tools. The youngest level of erectus remains at Zhoukoudian date from about 300,000 years ago. Another theory is a surviving Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), proposed by Myra Shackley. Neanderthal fossils are not known in Central Asia, though Shackley claims to have recovered, in Mongolia, Mousterian tools normally associated with them. Almas descriptions seem to indicate a more primitive morphology than known Neanderthal fossils, so Shackley has also theorized that they may represent a common ancestor to Neanderthals and modern humans.

Sources :

Hidden Histories of The Human Race by Michael Cremo;

Mysterious Creatures : “A Guide to Cryptozoology” by George M. Eberhart;

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Almas_%28cryptozoology%29

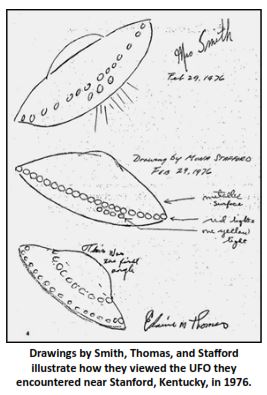

Pic source :

Mysterious Creatures : “A Guide to Cryptozoology” by George M. Eberhart page 12

After returning to Europe in 1427, Schiltenberger wrote about his experiences, which included wildmen. While in the Tian Shan Mountains, he became the first Westerner to see an Almas:

"In the mountains themselves live wild people, who have nothing in common with other human beings. A pelt covers the entire body of these creatures. Only the hands and face are free of hair. They run around in the hills like animals and eat foliage and grass and whatever else they can find."

Sometime in the late nineteenth century, a caravan was resting in the southern part of the Mongolian province of Övörhangay on the way to Hohhot, Nei Mongol Autonomous Region, China, one of the men in the party went to collect the camels that had been set loose to graze. When he did not return, the others went off into the saxaul thickets to look for him. At the entrance to a cave, they found evidence of a struggle and figured an Almas had abducted him. One of the elders suggested they pick him up on the way back from Hohhot, which they did, waiting until the creature emerged from the cave at sundown and shooting it. The rescued man seemed to be insane and died two months afterward.

Sometime in the late nineteenth century, a caravan was resting in the southern part of the Mongolian province of Övörhangay on the way to Hohhot, Nei Mongol Autonomous Region, China, one of the men in the party went to collect the camels that had been set loose to graze. When he did not return, the others went off into the saxaul thickets to look for him. At the entrance to a cave, they found evidence of a struggle and figured an Almas had abducted him. One of the elders suggested they pick him up on the way back from Hohhot, which they did, waiting until the creature emerged from the cave at sundown and shooting it. The rescued man seemed to be insane and died two months afterward.In April 1906, Soviet scholar Badzar Baradiin reportedly had a brief encounter with an Almas while he was traveling in the Gobi Desert near Badain Jaran, Nei Mongol Autonomous Region, China. However, Michael Heaney considers this story a fiction, based on the fact that there is no mention of the incident in Baradiin’s meticulous diary of the trip; moreover, the actual route was 150 miles east of where the event supposedly took place.

A seven-year-old Almas female was accidentally killed in the Gobi when she set off a crossbow attached to an animal snare. Many people in the sparsely populated area are said to have seen the body, but the locals begged investigators not to talk about it, since crossbow snares were illegal.

The Pamir mountains, lying in a remote region where the borders of Tadzhikistan, China, Kashmir, and Afghanistan meet, have been the scene of many Almas sightings. In 1925, Mikhail Stephanovitch Topilski, a major-general in the Soviet army, led his unit in an assault on an anti-Soviet guerilla force hiding in a cave in the Pamirs. One of the surviving guerillas said that while in the cave he and his comrades were attacked by several apelike creatures. Topilski ordered the rubble of the cave searched, and the body of one such creature was found. Topilski reported:

"At first glance I thought the body was that of an ape. It was covered with hair all over. But I knew there were no apes in the Pamirs. Also, the body itself looked very much like that of a man. We tried pulling the hair, to see if it was just a hide used for disguise, but found that it was the creature's own natural hair. We turned the body over several times on its back and its front, and measured it. Our doctor made a long and thorough inspection of the body, and it was clear that it was not a human being."

In 1927, travelers left a caravan unattended while they went to look for a camel that had dropped back. Upon their return at daybreak, they found several Almas warming themselves by the dying campfire. The creatures had eaten some dried dates and sweets but had left the jars of wine untouched.

A monk named Dambayorin was traveling across the Gobi in 1930 when he saw a naked child in the distance. When he got closer, he saw it was covered with red hair, realized it was an Almas, and fled in terror.

An entire skin of an Almas is said to have hung in the temple of the monastery at Baruun Hural, Mongolia, in 1937. It had humanlike legs and arms and long hair hanging from its head. The Almas had been killed in the Gobi by the hunter Mangal Durekchi and given to the lamas. A Mongolian pharmacist named Nagmit was in the mountains with two Kazakhs when they came upon an Almas. They shouted at it, offering it food and clothing, but it kept its distance. When they shot at it, intentionally missing, the creature merely seemed curious, then departed.

In 1957, Alexander G. Pronin, a hydrologist at the Geographical Research Institute of Leningrad University, participated in an expedition to the Pamirs, for the purpose of mapping glaciers. On August 2, 1957, while his team was investigating the Fedchenko glacier, Pronin hiked into the valley of the Balyandkiik River. Pronin stated:

"At noon I noticed a figure standing on a rocky cliff about 500 yards above me and the same distance away. My first reaction was surprise, since this area was known to be uninhabited, and second was that the creature was not human. It resembled a man but was very stooped. As i watched the stocky figure move across the snow, keeping its feet wide apart, and its forearms were longer than a human's and it was covered with reddish-grey hair."

Pronin saw the creature again three days later, walking upright. Since this incident, there have been numerous wildman sightings in the Pamirs, and members of various expeditions.

In 1963, Ivan Ivlov, a Russian pediatrician, was traveling through the Altai mountains in the southern part of Mongolia. Ivlov saw several humanlike creatures standing on a mountain slope. They appeared to be a family group, composed of a male, female, and child. Ivlov observed the creatures through his binoculars from a distance of half a mile until they moved out of his field of vision. His Mongolian driver also saw them and said they were common in that area. After his encounter with the Almas family, Ivlov interviewed many Mongolian children, believing they would be more candid than adults. The children provided many additional reports about the Almas. For example, one child told Ivlov that while he and some other children were swimming in a stream, he saw a male Almas carry a child Almas across it.

In 1980, a worker at an experimental agricultural station, operated by the Mongolian Academy of Sciences at Bulgan, encountered the dead body of a wildman:

"I approached and saw a hairy corpse of a robust humanlike creature dried and half-buried by sand. . . . The dead thing was not a bear or ape and at the same time it was not a man like Mongol or Kazakh or Chinese and Russian."

Possible explanations suggested by Mark Hall and Loren Coleman, perhaps the Almas is a surviving Homo erectus, The nearest known fossils are the Zhoukoudian Peking man remains found north of Beijing in the 1920s. The browridge, flat nose, absent chin, and robust jaw match Almas descriptions. H. erectus used a primitive (Acheulean) toolkit of hand axes and other bifacial stone tools. The youngest level of erectus remains at Zhoukoudian date from about 300,000 years ago. Another theory is a surviving Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), proposed by Myra Shackley. Neanderthal fossils are not known in Central Asia, though Shackley claims to have recovered, in Mongolia, Mousterian tools normally associated with them. Almas descriptions seem to indicate a more primitive morphology than known Neanderthal fossils, so Shackley has also theorized that they may represent a common ancestor to Neanderthals and modern humans.

Sources :

Hidden Histories of The Human Race by Michael Cremo;

Mysterious Creatures : “A Guide to Cryptozoology” by George M. Eberhart;

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Almas_%28cryptozoology%29

Pic source :

Mysterious Creatures : “A Guide to Cryptozoology” by George M. Eberhart page 12

Please don't put your website link in Comment section. This is for discussion article related only. Thank you :)